|

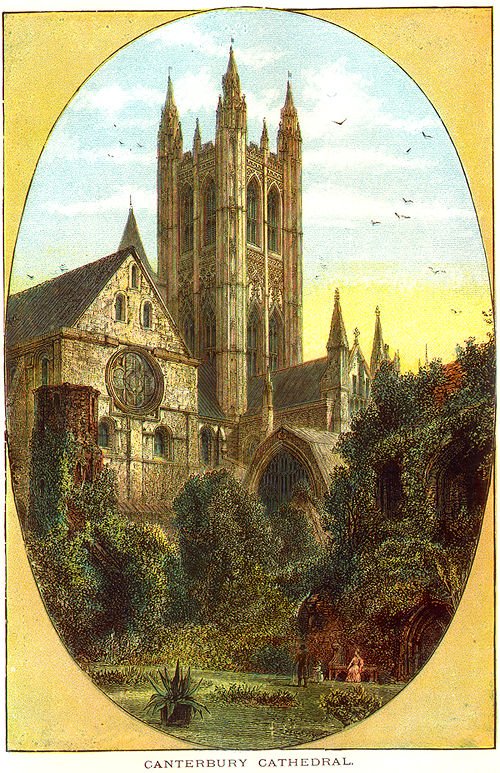

NCIENT, beautiful and full of historical memories is Canterbury Cathedral.

Here the first Christian Church erected by the AngloSaxons arose, and Canterbury

is the oldest Episcopal city in England. Its archbishop is metropolitan,

and has suffragan bishops subject to him; he is also primate of all England,

and first peer of the realm.

Many of the Roman legionaries were Christians, and they had built

two churches at Canterbury, which were still standing when Augustine arrived

at the court of the king of Kent. Every one knows how Gregory the Great,

enchanted with the beauty of the Anglo-Saxon children in the slave-market

where they were exposed for sale, despatched Augustine on a mission of conversion

to Britain. He (Augustine), decided on going to Canterbury first, because

Ethelbert's queen, the lovely Bertha of France, was a Christian, and had

stipulated when she married for the free exercise. of her religion, and for

a chaplain and some minor ecclesiastics to perform mass for her; the missionary

was consequently sure of a welcome from the royal lady and her priests. With

great pomp, and in solemn procession, Augustine and his forty attendant monks

presented themselves to the King and Queen of Kent. Ethelbert received them

courteously, and appointed them a residence in his chief city, Canter bury.

Very soon the king became a convert to Christianity and gave liberty to the

monks to preach freely and build churches throughout his kingdom, and Pope

Gregory declared that hereafter the Church of Canterbury was to be paramount

over all others in England, " for," said the good Pope, "where the Christian

faith was first received, there also should be a primacy of dignity."

On the death of Ethelbert the infant Church was exposed to great

perils. Ethelbert's son and successor, Eadbald, was a pagan and a persecutor;

the enemies of Christianity ruled in Kent, and the bishops of London and

Rochester, who had been appointed by Augustine, fled from the country, forsaking

their sees in order to save their lives. Bishop Lawrence, Augustine's successor,

was about to fly also, when he was stayed by a miracle, real or pretended.

The night before his intended departure Lawrence slept in the church,

and dreamed that the Apostle Peter appeared to him, and reproaching him severely

for his cowardice in forsaking the flock entrusted to his care, proceeded

to beat him severely with his pastoral staff. Lawrence awaking in pain, found

that a portion of his dream had been a reality, for he was stiff with bruises

and weals, and his shoulders were severely lacerated.

The bishop at once proceeded to the palace, asked to see the apostate

king, and laying bare his wounded shoulders, told Eadbald the vision. The

king became from that hour convinced of the truth of the Christian religion,

for be could not suppose that Lawrence would have willingly inflicted such

injuries on himself. If he had, or if he had ordered one of his monks to

do it, the pious fraud had greater success than it deserved, for the king

of Kent now supported the church he had persecuted.

Canterbury was sacked in after years by the Danes, who massacred

the archbishop and all his monks-for the church was also a monastic institution,

and the archbishop an abbot. Canute, to atone for this cruel sacrilege, repaired

the church and restored the body of the murdered archbishop to his monks. But

in the time of the Norman Conquest the church was completely burned down,

and not a single fragment remains of St. Augustine's Church.

Lanfranc rebuilt it and Anselm built the choir in such splendid

style that according to William of Malmesbury, "it surpassed every other

choir in England," in the transparency of its glass windows, its beautiful

marble pavement and the painting of the roof. Prior Conrad completed the

chancel, and the magnificent cathedral was dedicated in 1130, in the presence

of Henry I. of England, David, king of Scotland, and all the bishops of the

English Church.

In 1170 Becket was murdered in this church, and it was in Conrad's

choir that the monks watched his body the following night.

It is a sad story - a few hasty words spoken by the king, who had

certainly been greatly tried by the haughty prelate, and four knights, Reginald

Fitzurse, William Tracy, Hugh de Morville and Richard Brito set out to rid

Henry of his foe.

On the 29th of December they proceeded with a number of followers

and citizens to the Monastery of St. Augustine, the abbot of which was loyal

to the king; from thence they proceeded to the archbishop's palace, and entering

his apartment abruptly at about two in the afternoon, seated themselves on

the moor without saluting him in any way. There was a pause : then Becket

asked what they wanted; they did not answer immediately, but sat gazing on

him with haggard eyes. At length Reginald Fitzurse spoke: "We come," he said,

"that you may absolve the bishops you have excommunicated ; re-establish

the bishops you have suspended; and answer for your own offences against

the king."

Becket replied with boldness and great warmth, saying that he had

published the papal letters of excommunication with the king's consent; that

he could not absolve the Archbishop of York, whose case was heinous, and

must be brought before the Pope alone; but that he would remove the censures

from the two other bishops if they would swear to submit to the decisions

of Rome.

"But of whom, then, do you hold your archbishopric," asked Reginald

- "of the king or the Pope?"

"I owe the spiritual rights to God and the Pope, and the temporal

rights to the king," answered Becket.

"How! Is it not the king hath given you all?"

Becket replied in the negative; "and the knights furiously twisted

their long gloves."

Becket then reproached three of them, who had been his liegemen

in the days of his vainglory and prosperity, for forsaking him, and said

that it was not for such as they to threaten him in his own house, adding

that if he were threatened by all the swords in England he would not yield.

"We will do more than threaten," replied the knights, and departed.

When they were gone Becket's attendants blamed him for the rough and provoking

tone in which he had replied to his adversaries. He answered that he had

no need of their advice; he knew what to do. The barons, who seem to have

wished to avoid bloodshed, finding that threats were useless, armed themselves

and returned to the palace, but they found the gate had been shut and barred

by the servants. Robert de Broc endeavoured to break it in with his battle-axe,

and his blows rang on the air.

Becket's servants, greatly alarmed, besought him to escape, but

he refused even to take sanctuary in the church, perhaps from fear of the

holy place being contaminated by crime and bloodshed, but at last, as the

bell tolling for vespers reached his ears, he said he would go to the service,

and making his cup-bearer precede him with the crucifix uplifted, he passed

through the corridor with a solemn and measured pace, and entered the church.

His servants wished to barricade the doors, but Becket forbade them. "No

one," he said, "should be debarred from entering the house of God."

The terrified monks, as the noise outside became greater, fled

to hide themselves; only three-Canon Robert of Merton, Fitz Stephen, and

the faithful Gryme remained with him. He was ascending the steps that lead

to the choir when Reginald Fitzurse appeared at the west end of the church,

waving his sword and shouting, "Follow me, loyal servants of the king." The

other conspirators followed him closely; four mailed figures gleaming, whenever

a faint light from a shrine fell on their armour. But the shades of evening

were closing in the short December day, and the vast church was in obscurity.

Becket might easily have escaped and hidden himself in the intricate crypt

underground, or in the chapel beneath the roof, and the monks urged him to

do so, but he refused, and boldly advanced to meet the intruders, preceded

by his cross-bearer, Edward Gryme, or Grim, a German monk.

A voice shouted, "Where is the traitor? " Becket made no reply;

but when Fitzurse said, "Where is the archbishop?" he answered, "Here am

I, an archbishop, but no traitor, ready to suffer in my Saviour's name."

Tracy pulled him by the sleeve, saying, "Come, thou art our prisoner."

He pulled back his arm so violently that he made Tracy stagger.

"They advised him," says Knight in his "Pictorial History," "to

flee, or to go with them; and on a candid consideration it seems to us that

the conspirators are entitled to a doubt as to whether they really intended

a murder, or were not rather hurried into it by his obstinacy and provoking

language."

It does, indeed, seem as if Becket desired what he considered martyrdom.

Turning to Fitzurse he said, "I have done thee many pleasures, why comest

thou with armed men into my church?" They told him he must instantly absolve

the bishops. "Never, till they have offered satisfaction," he replied, and

he addressed a foul term to Fitzurse.

"Then die," exclaimed Fitzurse, striking at his head ; but the

faithful Gryme interposed his arm, which was nearly cut off, and the stroke

only just reached the primate, and slightly wounded him. Another voice cried,

"Fly, or thou diest!" but still Becket did not move. With the blood running

down his face, he clasped his hands, and bowing his head exclaimed, "To God,

to St. Mary, to the holy patrons of this church and to St. Denis, I commend

my soul and the Church's cause."

Blow now followed blow, and one from De Tracy brought him to the

pavement; another was given with such force that the sword broke against

the stone flooring. The blow had cleft his skull, and the brains were scattered

about. Hugh of Horsea, one of their followers, then put his foot on the archbishop's

neck, and cried, "Thus perishes a traitor."

The conspirators then left the church in safety, and went their

different ways.

There are memorials of Becket's assassination in the cathedral

itself. There is the Transept of Martyrdom ; the door by which the knights

entered the church ; the wall in front of which the archbishop fell, and

there is reason to believe (antiquarians tell us) that the pavement in front

of the wall is the same now as then. It is of hard Caen stone, and a small

square piece has been cut out of it, probably as a relic.

The steps up which pilgrims to the shrine of St. Thomas climbed

on their knees still remain ; and the indentations in the stones from wear

yet tell of the pious multitudes that sought from him protection or pardon.

In 1174 Canterbury Cathedral was on fire, and the whole of the

choir was destroyed. It was restored by William of Sens, and William Anglus,

i.e. English William, under whom the choir and other buildings were completed,

1184. Prior Challenden took down Lanfranc's nave, and erected a new one with

transepts, and Prior Goldstone added the great central tower.

In 1692 Canterbury suffered with all the other cathedrals. The

centre of the great window of the north transept, in which Becket was painted

robed and mitred, was demolished by a Roundhead.

The present cathedral, consisting of the different buildings thus

erected, combines specimens of all classes of pointed architecture-transition,

Norman, and perpendicular. The interior is much finer than the exterior.

It is in the form of a double cross, and consists of a nave and aisles, a

short transept with two chapels, a choir and aisles elevated above the nave

by a flight of steps, another and larger transept with two semicircular recesses

on the east side of each, and two square towers to the west

.

East of the choir is Trinity chapel, which contains Becket's shrine

and the corona, with the monument of Cardinal Pole.

Canterbury is distinguished from all other cathedrals by the choir

rising so high above the nave. It is reached by a stately flight of steps,

and this magnificent approach (with the massive piers rising like a forest

of stone) is one of the chief beauties of the great cathedral.

Pilgrimages to the shrine of Becket (who was canonised) were frequent

during the Middle Ages, and to them we owe the chief poems of our first English

poet, Chaucer, the "Canterbury Tales." The murder of Becket and his following

canonisation, were indeed most important events in the history of the cathedral.

To him it owed its fame and wealth and artistic decorations.

The great window of the north transept was, as we have said, destroyed

by a Roundhead, named Richard Culmer or Blue Dick, with his pike; the destructive

Puritan, however, narrowly escaped with his life, for a loyal fellow-townsman

threw a stone at him with so good an aim that, if Blue Dick had not ducked,

he might have laid his bones there.

There is still existing a grace cup, believed to have belonged

to Becket, and legends and initials confirm the ancient possessorship. Round

the lid is the motto Sobrii estate, with the letters T. B. support ing a

mitre. Round the cup is chased Vinum tuum bibe cum gaudio. Round the neck

is the name " God Ferare," probably the name of the goldsmith. The cup of

ivory probably did belong to Becket, but the setting is not earlier than

towards the close of the fifteenth century.

It is in the possession of the Arundel family.

|

|