Contents |

|

About this site |

|

Download the Cyclopedia |

|

Awards |

|

Links | |

|

|

Persons unaccustomed to serving at table will, with the help of these cuts, and the instructions accompanying them, soon be able to carve well: if, at the same time, they will, as occasion offers take notice how a good carver proceeds when a joint or fowl is before him.

We will begin with those joints etc., that are simple and easy to be carved, and afterwards proceed to such as are more complicate and difficult.

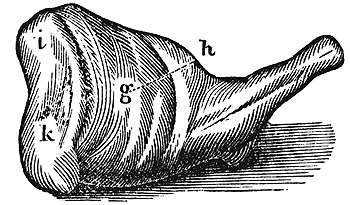

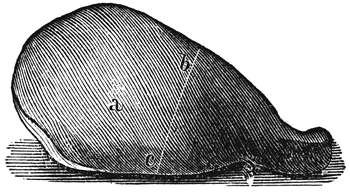

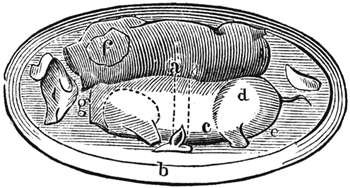

This cut represents a leg or jigot of boiled mutton; it should be served up in the dish as it lies lying upon its back; but when roasted, the under side, as here represented by the letter d, should lie uppermost in the dish, as in a ham (which see); and in this case, as it will be necessary occasionally to turn it, so as to get readily at the under side, and cut it in the direction of a b, the shank, which is here broken and bent for the convenience of putting it into a less pot or vessel to boil it, is not broken or bent in a roasted joint, of course should be wound round (after it is taken off the spit) with half a sheet of writing paper, and so sent up to table that a person carrying it may take hold of it without greasing his hands. Accordingly, when he wishes to cut it on the under side, it being too heavy a joint to be easily turned with a fork, the carver is to take hold of the shank with his left hand, and he will thus be able to turn it readily, so as to out it where he pleases with his right.

A leg of wether mutton, which is by far the best flavored, may be readily known when bought, by the kernel, or little round lump of fat, just above the letters a e.

When a leg of mutton is first cut, the person carving should turn the joint towards him, as it here lies, the shank to the left hand; then holding it steady with his fork, he should cut in deep on the fleshy part, in the hollow of the thigh, quite to the bone, in the direction a b. Thus will he cut right through the kernel of fat, called the pope's eye, which many are fond of. The most juicy parts of the leg are in the thick part of it, from the line a b, upwards towards e, but many prefer the drier part, which is about the shank or knuckles; this part is by far the coarser, but as I said, some prefer it, and call it the venison part, though it is less like venison than any other part of the joint. The fat of this joint lies chiefly on the ridge e e, and is to be cut in the direction e f.

In a leg of mutton there is but one bone readily to be got at, and that a small one, this is the cramp-bone, by some called the gentleman's bone, and is to be cut out by taking hold of the shank-bone with the left hand, and with a knife cutting down to the thigh-bone at the point d. then passing the knife under the cramp-bone, in the direction d c, it may easily be cut out.

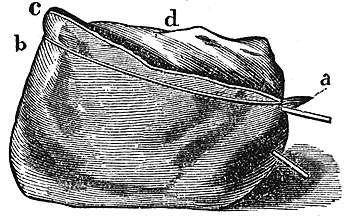

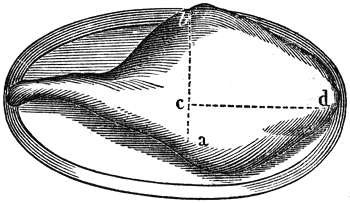

Figure 1 represents a shoulder of mutton, which is sometimes salted and boiled by fanciful people; but customarily served up roasted, and laid in a dish, with the back or upper side uppermost, as here represented.

When not over-roasted it is a joint very full of gravy, much more so than a leg, and as such by many preferred, and particularly as having many very good, delicate, and savory parts in it.

The shank-bone should be wound round with writing paper, as pointed out in the leg, that the person carving may take hold of it to turn it as he wishes. Now, when it is first cut, it should be in the hollow part of it, in the direction a b, and the knife should be passed deep to the bone. The gravy then runs fast into the dish, and the part cut opens wide enough to take many slices from it readily,

The best fat, that which is full of kernels and best flavored, lies on the outer edge, and is to be cut out in thin slices in the direction e f. If many are at table, and the hollow part, cut in the line a b, is all eaten, some very good and delicate slices may be cut out on each side of the ridge of the blade-bone, in the direction c d. The line between these two dotted lines is that in the direction of which the edge or ridge of the blade bone lies, and cannot be cut across.

On the under side of the shoulder, as represented in figure 2, there are two parts very full of gravy, and such as many person' prefer to those of the upper side. One is a deep cut in the direction g h, accompanied with fat, and the other all lean in a line from i to k. The parts about the shank are coarse and dry, as about the knuckle in the leg but yet some prefer this dry part, as being less rich or luscious, and of course less apt to cloy.

A shoulder of mutton over-roasted is spoiled.

Whether boiled or roasted, is sent up to table as a leg of mutton roasted, and cut up in the same manner; of course I shall refer you to what I have said on that joint, only that the close firm flesh about the knuckle is by many reckoned the best, which is not the case in a leg of mutton.

Is never cut or sent to table as such, but the shankbone, with some little meat annexed, is often served up boiled, and called a spring, and is very good eating.

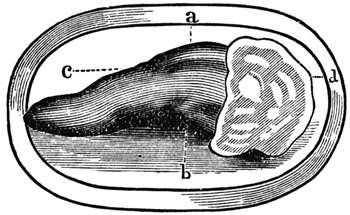

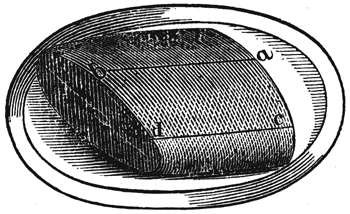

In carving it, as the outside suffers in its flavor from the water in which it is boiled, the dish should be turned towards the carver, as it is here represented, and a thick slice should be first cut off the whole length of the joint, beginning at a and cutting it all the way even and through the whole surface, from a to b.

The soft fat that resembles marrow lies on the back below the letter d, and the firm fat is to be cut in thin horizontal slices at the point c; but as some persons prefer the soft fat and others the firm, each should be asked what he likes.

The upper part, as here shown, is certainly the handsomest, fullest of gravy, most tender, and is encircled with fat, but there are still some who prefer a slice on the under side, which is quite lean. But as it is a heavy joint and very troublesome to turn, that person cannot have much good manners who requests it.

The skewer that keeps the meat together when boiling is here shown at a. It should be drawn out before the dish is served up to table, or if it be necessary to leave a skewer in, that skewer should be a silver one.

A knuckle of veal is always boiled, and is admired for the fat, sinewy tendons about the knuckle, which, if boiled tender, are much esteemed. A lean knuckle is not worth the dressing.

You cannot cut a handsome slice, but in the direction a b. The most delicate fat lies about the part d, and if cut in the line d c, you will divide two bones, between which lies plenty of fine, marrowy fat.

The several bones about the knuckle may be readily separated at the joints, and, as they are covered with tendons, a bone may be given to those who like it.

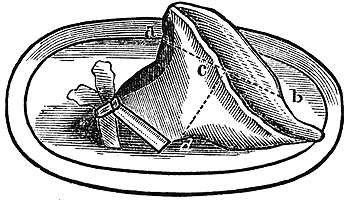

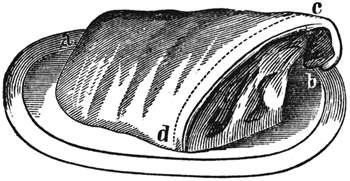

This is the best end of a breast of veal, with the sweetbread lying on it, and, when carved, should be first out down quite through in the first line on the left, d c; it should next be cut across in the line a c; from c to the last a on the left, quite through divides the gristles from the rib-bones; this done, to those who like fat and gristle, the thick or gristly part should be cut into pieces as wanted, in the lines a b. When a breast of veal is cut into pieces and stewed, these gristles are very tender and eatable. To such persons as prefer a bone a rib should be cut or separated from the rest in the line d c, and with a part of the breast, a slice of the sweetbread, e, cut across the middle.

This is by some called a chine of mutton, the saddle being the two necks; but as the two necks are now seldom sent to table together, they call the two loins a saddle.

A saddle of mutton is a genteel and handsome dish; it consists of the two loins together, the back-bone running down the middle to the tail. Of course, when it is to be carved, you must cut a long slice in either of the fleshy parts on the side of the back-bone, in the direction a b.

There is seldom any great length of the tail left on, but if it is sent up with the tail many are fond of it, and it may readily be divided into several pieces by cutting between the joints of the tail, which are about the distance of one inch apart.

A saddle of venison is cut similarly to the above.

A spare-rib of pork is carved by cutting out a slice from the fleshy part in the line a b. This joint will afford many good cuts in this direction with as much fat as people like to eat of such strong meat. When the fleshy part is cut away, a bone may be easily separated from the next to it in the line d b c, disjointing it at c.

There are many delicate bits about a calf's head, and when young, perfectly white, fat and well dressed, half a head is a genteel dish, if a small one.

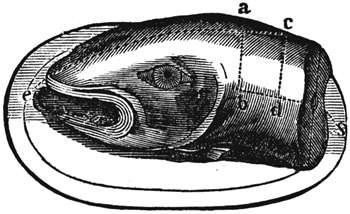

When first cut it should be quite along the cheek bone, in the fleshy part, in the direction c b, where many handsome slices may be cut. In the fleshy part at the end of the jaw-bone, lies part of the throat sweetbread, which may be cut into in the line c d, and which is esteemed the best part in the head. Many like the eye, which is to be cut from its socket a, by forcing the point of a carving knife down to the bottom on one edge of the socket, and cutting quite round, keeping the point of the knife slanting towards the middle, so as to separate the meat from the bone. This piece is seldom divided, hut if you wish to oblige two persons with it, it may be cut into two parts; the palate is also reckoned by some a delicate morsel. This is found on the under side of the roof of the mouth; it is a crinkled, white, thick skin, and may be easily separated from the bone by the knife by lifting the head up with your left hand.

There is also some good meat to be met with on the under side, covering the under jaw and some nice gristly fat to be pared off about the ear, g.

There are scarcely any bones here to be separated, but one may be cut off at the neck, in the line f e, but this is a coarse part.

There is a tooth in the upper jaw, the last tooth behind, which, having several cells, and being full of jelly, is called the sweet tooth. Its delicacy is more in the name than in anything else. It is a double tooth, lies firm in its socket at the further end, but if the calf is a young one, may readily be taken out with the point of a knife.

A ham is cut two ways; across, in the line b e or with the point of a carving knife, in the circular line in the middle, taking out a small piece as at a, and cutting thin slices in a circular direction thus enlarging it by degrees. This last method of cutting it is to preserve the gravy and keep it moist, which is thus prevented from running out.

In carving a haunch of venison, first cut it across down to the bone, in the line d c a, then turn the dish with the end a towards you, put in the point of the knife at c, and cut it down as deep as you can in the direction c b; thus cut, you may take out as many slices as you please, on the right or left. As the fat lies deeper on the left between b and a, to those who are fond of fat as most venison eaters are, the best flavored and fattest slices will be found on the left of the line c b, supposing the end a turned towards you. Slices of venison should not be cut thick nor too thin; and plenty of gravy should be given with them.

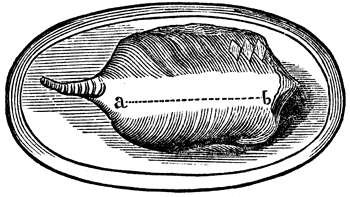

A tongue is to be cut across, in the line a, b, and a slice taken from thence. The most tender and juicy slices will be about the middle, or between the line a b, and the root. Towards the tip, the meat is closer and dryer, For the fat, and a kernel with that fat, cut off a slice of the root on the right of the letter b, at the bottom next the dish. A tongue is often cut lengthways, as from c to d. A tongue is generally eaten with white meat, veal, chicken, or turkey, and to those whom you serve with the latter, you should give of the former.

This is a part always boiled, and is to be cut in the direction of a b, quite down the bone, but never help any one to the outside slice, which should be taken off pretty thick. The fat cut with this slice is a firm gristly fat, but a softer fat will be found underneath, for those who prefer it.

Whether the whole sirloin, or part of it only, be sent to table, is immaterial, with respect to carving it. The figure here represents part of the joint only, the whole being too large for families, in general. It is drawn as standing up in the dish, in order to show the inside or under part: but when sent to table, it is always laid down, so as that the part described by the letter c lies close on the dish. The part e d then lies uppermost and the line a b underneath.

The meat on the upper side of the ribs is firmer and of a closer texture than the fleshy part underneath, which is by far the most tender; of course, some prefer one part, and some another.

To those who like the upper side, and would rather not have the first cut or outside slice, that outside slice should be first cut off, quite down to the bone, in the direction c d. Plenty of soft marrowy fat will be found underneath the ribs. If a person wishes to have a slice underneath, the joint must be turned up, by taking hold of the end of the ribs with the left hand, and raising it until it is in the position as here represented. One slice or more may now be cut in the direction of the line a b, passing the knife down to the bone. The slices, whether on the upper or under side, should be cut thin, but not too much so.

Is always boiled, and requires no print to point out how it should be carved. A thick slice should be out off all round the buttock, that your friends may be helped to the juicy and prime part of it. This cut into, thin slices may be cut from the top; but as it is a dish that is frequently brought to the table cold a second day, it should always be cut handsome and even. To those to whom a slice all round would be too much, a third of the round may be given, with a thin slice of fat. On one side there is a part whiter than ordinary, by some called the white muscle. A buttock is generally divided, and this white part sold separate as a delicacy, but it is by no means so, the meat being close and dry, whereas the darker colored parts., though apparently of a coarser grain, are of a looser texture, more tender, fuller of gravy, and better flavored; and men of discriminating palates ever prefer them.

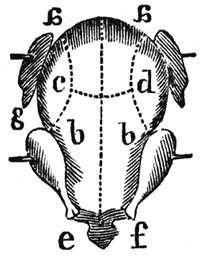

Before any one is helped to a part of this joint, the shoulder should be separated from the breast, or what is by some called the coast, by passing the knife under, in the direction c g d e. The shoulder being thus removed, a lemon or orange should be squeezed upon the part, and then sprinkled with salt where the shoulder joined it, and the shoulder should be laid on it again. The gristly part should next be separated from the ribs, in the line f a. It is now in readiness to be divided among the company.. The ribs are generally most esteemed, and one or two may be separated from the rest, in the line a b; or, to those who prefer the gristly part, a piece or two, or more, may be cut off in the lines h i, etc. Though all parts of young lamb are nice, the shoulder of a fore-quarter is least thought of; it is not so rich.

If the fore-quarter is that of a grass lamb and large, the shoulder should be put into another dish when taken off; and it is carved as a shoulder of mutton, which see.

Which is the thigh part, similar to a buttock of beef, is brought to table always in the same form, but roasted. The outside slice of the fillet is by many thought a delicacy, as being most savory; but it does not follow that every one likes it; each person should therefore be asked, what part he prefers. If not the outside cut off a thin slice, and the second cut will be white meat, but cut it even and close to the bone. A fillet of veal is generally stuffed under the skirt or nap with a savory pudding, called forcemeat. This is to be cut deep into, in a line with the surface of the fillet, and a thin slice taken out; this, with a little fat cut from the skirt, should be given to each person present.

A roasted pig is seldom sent to table whole, the bead is cut off by the cook, and the body slit down the back and served up as here represented, and the dish garnished with the chaps and ears.

Before any one is helped, the shoulder should be separated from the carcass, by passing the knife under it, in the circular direction; and the leg separated in the same manner, in the dotted lines c d c. The most delicate part in the whole pig is the triangular piece of the neck, which may be cut off in the line f g. The next best parts are the ribs, which may be divided in the line, a b, etc. Indeed, the bones of a pig of three weeks old are little less than gristle, and may be easily cut through, next to these, are pieces cut from the leg and shoulder. Some are fond of an ear, and others of a chap, and those persons may readily be gratified.

This is a rabbit, as trussed and sent up to table. After separating the legs, the shoulders or wings (which many prefer) are to be cut off in the circular dotted line e f g. The back is divided into two or three parts, in the knee i k, without dividing it from the belly, but cutting it in the line g h. The head may be given to any person who likes it, the ears being removed before the rabbit is served up.

Like a turkey, is seldom quite dissected, unless the company is large; but when it is, the following is the method: Turn the neck towards you, and cut two or three long slices, on each side the breast, in the lines a b, quite to the bone. Cut these slices from the bone, which done, proceed to take off the leg, by turning the goose up on one side, petting the fork through the small end of the leg bone, pressing it close to the body, which, when the knife is entered at d, raises the joint from the body. The knife is then to be passed under the leg in the direction d e. If the leg hangs to the carcass at the joint e, turn it back with the fork, and it will readily separate if the goose is young; in old geese, it will require some strength to separate it. When the leg is off, proceed to take off the wing, by passing the fork through the small end of the pinion, pressing it close to the body, and entering the knife at the notch e, and passing it under the wing in the direction c, d. It is a nice thing to hit this notch e, as it is not so visible in the bird as in the figure. If the knife is put into the notch above it you cut upon the neck-bone and not on the wing-joint. A little practice will soon teach the difference; and if the goose is young the trouble is not great, but very much otherwise if the bird is an old one.

When the leg and wing on one side are taken off, take them off on the other side, cut off the apron in the line f e g, and shall take off the merry-thought in the line i h. The neck-bones are next to be separated as in a fowl, and all other parts divided as there directed, to which I refer you.

The best parts of a goose are in the following order: the breast slices; the fleshy part of the wing, which may be divided from the pinion; the thigh-bone, which may be easily divided in the joint from the leg-bone, or drumstick, as it it called; the pinion, and next the side-bones.

Is cut up in the same way, but the most delicate part is the breast and the gristle, at the lower part of it the pheasant, as here represented, is skewered and trussed for the spit, with the head tucked under one of the wings, tent when sent to table the skewers are withdrawn.

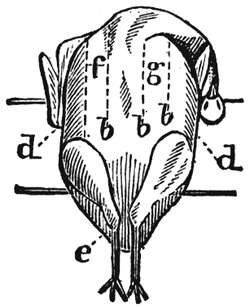

In carving this bird, the fork should be fixed in the breast, in two dots there marked. You have then the command of the fowl, and can turn it as you please; slice down the breast in the lines a b, and then proceed to take off the leg on the outside, in the direction d e, or in the circular dotted line b d, as seen in the figure "a boiled fowl," next page. Then cut off the wing on the same side in the line c d, in the figure above, and a b, in the figure at the bottom of this column, which is lying on one side, with its back towards us. Having separated the leg and wing on one side, do the same on the other, and then cut off or separate from the breast-bone on each side of the breast the parts you before sliced or cut down. In taking off the wing be attentive to cut it in the notch a' as seen in the print of the fowl, for if you cut too near the neck, as at g, you will find the neck-bone interfere. The wing is to be separated from the neck-bone. Next cut off the merrythought in the line f g, by passing the knife under it towards the neck. The remaining parts are to be cut up, us is described in the fowl, which see.

The partridge, like the pheasant, is here trussed for the spit; when served up the skewers are withdrawn. It is cut up like a fowl (which see), the wings taken off in the lines a b, and the merrythought in the lines c d. Of a partridge the prime parts are the white ones, viz., the wings, breast, merry-thought. The wing is thought the best, the tip being reckoned the most delicate morsel of the whole.

The fowl is here represented as lying on its side, with one of the legs, a wing and a neck-bone taken off. It is cut up the same way, whether it be roasted or boiled. A roasted fowl is sent to table trussed like a pheasant (which see), except that instead of the head being tucked under one of the wings, it is, in a fowl, cut off before it is dressed, A boiled fowl is represented below, the leg-bones of which are bent inwards and tucked in within the belly, but the skewers are withdrawn prior to its being sent to the table. In order to cut up a fowl, it is best to take it on your plate.

Having shown how to take off the legs, wings and merrythought, when speaking of the pheasant, it remains only to show how the other parts are divided: k is the wing cut off, i the leg. When the leg, wing and merry-thought are removed, the next thing is to cut off The neck-bones described at 1. This is done by putting in the knife at g, and passing it under the long, broad part of the bone in the line g h, then lifting it up and breaking off the end of the shorter part of the bone which cleaves to the breast-bone. All parts being thus separated from the carcass, divide the breast from the back by cutting through the tender-ribs on each side, from the neck quite down to the vent or tail. Then lay the back upwards on your plate, fix your fork under the rump, and laying the edge of your knife in The line b e c, and pressing it down lift up the tail or lower part of the back, and it will readily divide with the help of your knife in the line b e c. This done, la, the croup or lower part of the buck upwards is your plate, with the rump from you, and with your knife cut off the side-bones by forcing the knife through the rump-bone in the lines e f, and the whole fowl is completely carved.

Of a fowl, the prime parts are the wings, breast and merry-thought, and next to these the neckbones and sidebones; the legs are rather coarse; of a boiled fowl the legs are rather more tender' but of a chicken every part is juicy and good, and next to the breast the legs are certainly the fullest of gravy and the sweetest, and as the thigh-bones are very tender and easily broken with the teeth, the gristles and marrow render them a delicacy. Of the leg of a fowl The thigh is much the best and when given to any one of your company it should be separated from the drum-stick at the joint i (see the cut, viz., "a fowl," preceding column), which is easily done if the knife is introduced underneath in the hollow, and the thighbone turned back from the leg-bone.

Roasted or boiled, is trussed and sent up to table like a fowl, and cut up in every respect like a pheasant. The best parts are the white ones - the breast, wings and neckbones. Merry-thought it has none, the neck is taken away and the hollow part under the breast stuffed with forcemeat, which is to be cut in thin slices in the direction from the rump to the neck and a slice given with each piece of turkey. It is customary not to cut up more than the breast of this bird, and, if any more is wanted, to take off one of the wings.

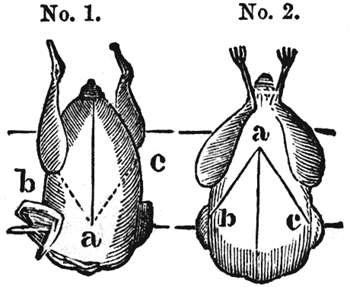

This is a representation of the back and breast of a pigeon. No. 1, the back; No. 2, the breast. It is sometimes cut up as a chicken, but as the croup, or lower part with the thigh, is most preferred, and as a pigeon is a small bird, and half a one not too much to serve at once, it is seldom carved now, otherwise than by fixing the fork at the point a, entering the knife just before it, and dividing the pigeon into two, cutting away in the lines a b, and a c, No. 1; at the same time bringing the knife out at the back in the direction a b, and a c, No. 2.

Fish, in general, requires very little carving; the middle or thickest part of the fish is generally esteemed the best except in a carp, the most delicate part of which is the palate. This is seldom however, taken out, but the whole head is given to those who like it. The thin part about the tail of a fish is generally least esteemed.

A cod's head and shoulders, if large and in season is a very genteel and handsome dish, if nicely boiled. When cut, it should be done with a spoon or fish trowel. The parts about the back-bone, on the shoulders, are the most firm and best, Take off a piece quite down to the bone, in the direction a b d c. putting in the spoon at a c, and with each slice of fish give a piece of the sound, which lies underneath the back-bone and lines it, the meat of which is thin and a little darker colored than the body of the fish itself: this may be got by passing a knife or spoon underneath, in the direction d a.

There are a great many delicate parts about the head, some firm kernels, and a great deal of the jelly kind; the jelly parts lie about the jawbone, the firm parts within the head, which must be broken into with a spoon. Some like the palate and some the tongue, which likewise may be got by putting the spoon into the mouth, in the direction of the line e s. The green jelly of the eye is never given to any one.

Of boiled salmon there is one part more fat and rich than the other. The belly part is the fattest of the two, and it is customary to give to those that like both a thin slice of each; for the one, cut it out of the belly part, in the direction d c; the other, out of the buck, in the line a b. Those who are fond of salmon generally like the skin; of course, the slices are to be cut thin, skin and all.

There are but few directions necessary for cutting up and serving fish. In turbot the fish-knife or trowel is to be entered in the centre or middle, over the backbone, and a piece of the flesh, as much as will lie on the trowel, to be taken off on one side close to the bones. The thickest part of the fish is always most esteemed, but not too near the head or tail; and when the meat on one side of the fish is removed close to the bones, the whole back-bone is to be raised with the knife and fork, And the under side is there to be divided among the company. Turbot eaters esteem the fins a delicate part,

The rock-fish and sheepshead are carved like the turbot. The latter is considered the most delicate fish of the Atlantic coast; and The former, though common, are highly esteemed, particularly those caught in fresh water.

The halibut is also frequently brought to market. The fins and parts lying near them are of a delicate texture and flavor; the remaining part of the fish is coarse.

Soles are generally sent to table two ways, some fried, others boiled; these are to be cut right through the middle, bone and all, and a piece of the fish, perhaps a third or fourth part, according to its size, given to each. The same may be done with other fishes, cutting them across, as may be seen in the cut of the mackerel, below d e c b.

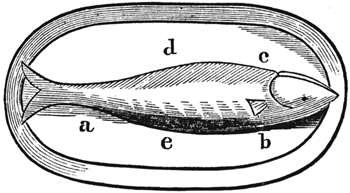

A mackerel is to be thus cut - slit the fish all along the back with a knife, in the line a e b, and take off one whole side as far as the line b c, not too near the head, as the meat about the gills is generally black and ill flavored. The roe of a male fish is soft like the brain of a calf, the roe of the female fish is full of small eggs and hard. Some prefer one and some another, and part of such roe as your friend likes should be given to him.

The meat about the tail of all fish is generally thin and less esteemed, and few like the head of a fish, except it be that of a carp, the palate of which is esteemed the greatest delicacy of the whole.

Eels are cut into pieces through the bone, and the thickest part is reckoned the prime piece.

There is some art in dressing a lobster, but this is seldom sent up to table whole, I will only say that the tail is reckoned the prime part, and next to this the claws.

We conclude the foregoing treatise on the Art of Carving by the following instructions, intended to aid housekeepers in the purchase of the most common descriptions of meat for the table.

If the flesh of ox-beef is young, it will have a fine smooth open grain, be of a good red and feel tender. The fat should look white rather than yellow; for when that is of a deep color the meat is seldom good; beef fed by oil cakes is in general so, and the flesh is flabby. The grain of cow-beef is closer, and the fat whiter, than that of oxbeef, but the lean is not of so bright a red. The grain of bull-beef is closer still, the fat hard and skinny, the lean of a deep red and a stronger scent. Ox-beef is the reverse. Ox-beef is the richest and largest; but in small families and to some tastes, heifer-beef is better if finely fed. In old meat there is a streak of horn in the ribs of beef; the harder this is, the older, and the flesh is not finely flavored.

The flesh of a bull calf is firmest but not so white. The fillet of the cow calf is generally preferred for the udder. The whitest is not the most juicy, having been made so by frequent bleeding, and having bad whiting to lick. Choose the meat of which the kidney is well covered with white thick fat. If the bloody vein in the shoulder looks blue or of a bright red, it is newly killed but any other color shows it stale. The other parts should be dry and white; if clammy or spotted the meat is stale and bad. The kidney turns first in the loin, and the suet will not then be firm.

Choose this by the fineness of its grain, good color, and firm white fat. It is not the better for being young; if of a good breed and well fed, it is better for age; but this only holds with wether mutton; the flesh of the ewe is paler, and the texture finer. Ram mutton is very strong flavored, the flesh is of a deep red, and the fat is spongy.

Observe the neck of a fore-quarter: if the vein is bluish it is fresh, if it has a green or yellow cast it is stale. In the hind-quarter if there is a faint smell under the kidney, and the knuckle is limp, the meat is stale. If the eyes are sunk, the head is not fresh. Grass-lamb comes into season in April or May, and continues till August. House-lamb may be had in great towns almost all the year, but is in highest perfection in December and January.

Pinch the lean, and if young it will break. If the rind is tough, thick, and cannot easily be impressed by the finger, it is old. A thin rind is merit in all pork. When fresh the flesh will be smooth and cool; if clammy it is tainted. What is called measly pork is very unwholesome, and may be known by the fat being full of kernels, which in good pork is never the case. Pork fed at still-houses does not answer for curing any way, the fat being spongy. Dairy-fed pork is the best.

If young, has a smooth black leg, with a short spur. The eyes full and bright if fresh, and the foot supple and moist. If stale, the eyes will be sunk and the feet dry. A hen-turkey is known by the same rules, but if old her legs will be red and rough.

If a cook is young, his spurs will be short; but take care to see they have not been cut or pared, which is a trick often practiced. If fresh the vent will be close and dark. Pullets are best just before they begin to lay and yet are full of eggs; if old hens, their combs and legs will be rough; if young, they will be smooth. A good capon has a thick belly and a large rump; there is a particular fat at his breast, and the comb is very pale. Black-legged fowls are most moist, if for roasting.

The bill and feet of a young one will be yellow, and there will be but few hairs upon them; if old, they will be red, if fresh, the feet will be pliable if stale, dry and stiff. Geese are called green till three or four months old. Green geese should be scalded; a stubblegoose should be picked dry.

Choose them by the same rules of having supple feet, and by their being hard and thick on the breast and belly; the feet of a tame duck are thick, and inclining to dusty yellow; a wild one has the feet reddish and smaller than the tame. They should be picked dry.

Ducklings must be scalded.

If good, they are white and thick. If too fresh they eat tough, but must not be kept above two days without salting.

If good, their gills are of a fine red, and the eyes bright, as is likewise the whole fish, which must be stiff and firm.

If they have not been long taken the claws will have a strong motion when you put your finger on the eyes and press them. The heaviest are the best. The cock-lobster is known by the narrow back part of his tail, and the two uppermost fins within it are stiff and hard, but those of the hen are soft, and the tail broader. The male, though generally smaller, has the highest flavor, the flesh is firmer, and the color when boiled is a deeper red.

The heaviest are best, and those of a middling size are sweetest. If light they are watery; when in perfection the joints of the legs are stiff, and the body has a very agreeable smell. The eyes look dead and loose when stale.

When alive and strong the shell is close. They should be eaten as soon as opened, the flavor becoming poor otherwise.

The abundance and variety of fish daily brought to market in every seaport town of the United States, cannot be surpassed in any other part of the world.

|